Last month, a delegation of 350 US and local group organizers traveled to West Virginia to learn more from partners on-the-ground about what climate organizing looks like in 2023 in a part of the country that has been so dominated by coal, it has practically become a language.

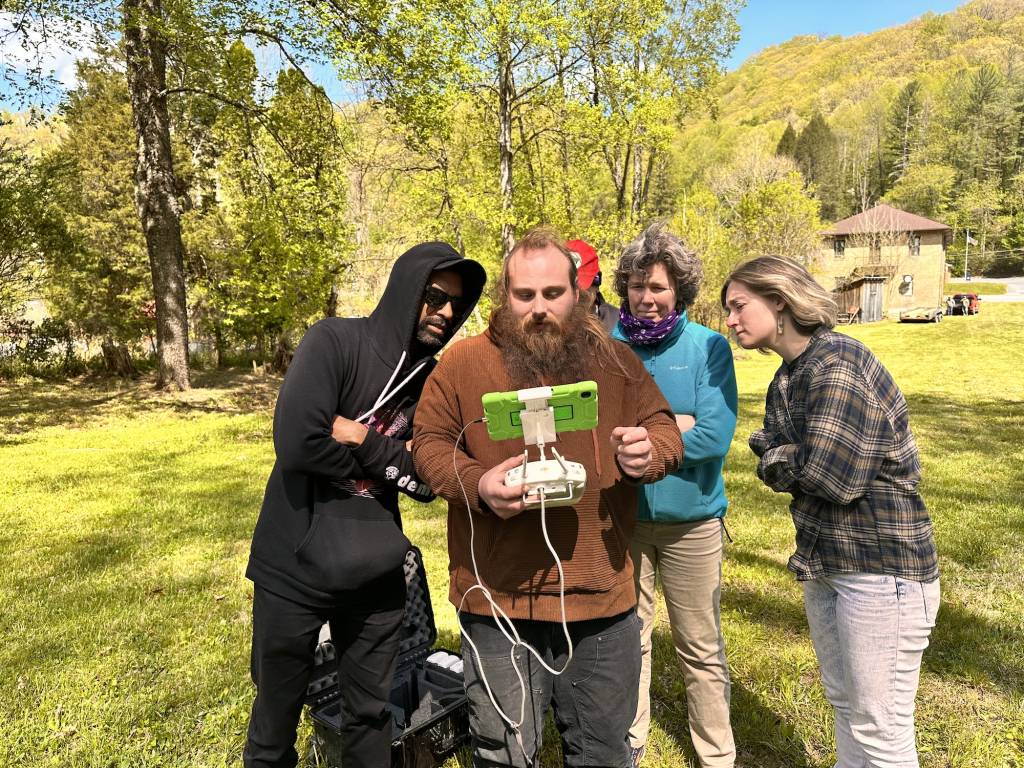

[pictured above (L-R)]: Candice Fortin, 350 US Campaign Manager (front); Laurel Levin, 350 Network Council (back); Jeff Ordower, 350.org North America Director; Kendra Ford, 350 NH; Nico Udu-gama, 350 US Senior Partnerships Coordinator; Junior Walk, CRMW Outreach Coordinator (back) and his partner Lee Edwards (front)

[pictured above (L-R)]: Candice Fortin, 350 US Campaign Manager (front); Laurel Levin, 350 Network Council (back); Jeff Ordower, 350.org North America Director; Kendra Ford, 350 NH; Nico Udu-gama, 350 US Senior Partnerships Coordinator; Junior Walk, CRMW Outreach Coordinator (back) and his partner Lee Edwards (front)

Coal River Mountain Watch and a brief history of mountaintop removal in WV

The 350 group met with Coal River Mountain Watch (CRMW) in the town of Naoma, in West Virginia’s Appalachian mountains. CRMW started in 1998 as a response to the widespread destruction of lands, rivers, and homes caused by mountaintop removal (MTR).

Companies claim to meet “reclamation” standards to restore the mountain. But by coal company standards, reclamation usually yields nothing beyond spraying grass seed on the mountainside, which does little to restore the flora and fauna and has visibility failed to prevent erosion.

Junior Walk, CRMW’s outreach coordinator, grew up in these mountains. When Junior was in school, his teachers told him not to worry about math, because his destiny—along with all of his classmates—was to work in coal.

This mentality runs deep—there is a strong cultural connection to coal, despite the negative environmental impacts, because it has formed the basis of the economy and has been such an integrated part of the community for generations. Yet that same long history has included an ongoing fight for living wages and dignity, even when coal was booming.

The largest labor uprising in US history took place on this land over one hundred years ago at the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, in which 10,000 miners fought the state for the right to unionize. The intersection and labor and environmental struggles continued into the 2000s and 2010s with the Appalachia Rising/Stop Mountaintop Removal mobilizations.

In the early 2000s, CRMW helped lay the groundwork for some of the grassroots power that defines the successful fossil fuel activism we know today. CRMW and Mountain Justice Summer brought students into coal country to educate them and begin an annual action, which moved hundreds of young people into the fight in Appalachia. This grew into years of sustained direct action, and ultimately led to the entire student divestment network, as students sought to fight coal investment at their schools.

CRMW and partner groups helped kick off a wave of activism that spread across the U.S., helping inform many of the direct action pipeline fights we know today. Their work also helped change the narrative around coal as an energy source. They continue that narrative work today, using aerial drone footage to monitor mine sites for violations, and educating student groups about MTR.

[pictured above]: Junior Walk demonstrating how he uses drones to monitor coal mine missions and mountaintop removal sites

[pictured above]: Junior Walk demonstrating how he uses drones to monitor coal mine missions and mountaintop removal sites

What does it look like to live in West Virginia coal country in 2023?

CRMW and their partners have definitely helped shift the narrative around coal nationally, but they pay a price locally. Junior faces constant harassment and intimidation from coal mine security and people who are told that he is trying to take away their jobs. When activists like Junior try to mobilize at mine sites and spread awareness, they often have to contend with law enforcement.

They also face misinformation weaponized by fossil fuel proponents. For example, even if mountaintop removal were not disastrous for the environment and for the people losing homes and land to the process, the reality is that it is not a substantial source of employment—the process is highly mechanized, and thus, mines only employ a few highly-skilled workers who generally come from outside the local area.

And for all residents of Naoma, no matter what “side” they are on? The closest hospital is an hour away. The landscape is increasingly barren. Fresh produce is hard to come by. And they are surrounded by “impoundment dams” holding coal slurry, a byproduct of the treatment of raw coal, which contains black water. These dams are prone to breaking, like one did in 1972 in Buffalo Creek, killing 125 people and leaving thousands homeless. Those who remain face high rates of cancer, contaminated drinking water, black lung disease, and a feeling of profound abandonment by the state.

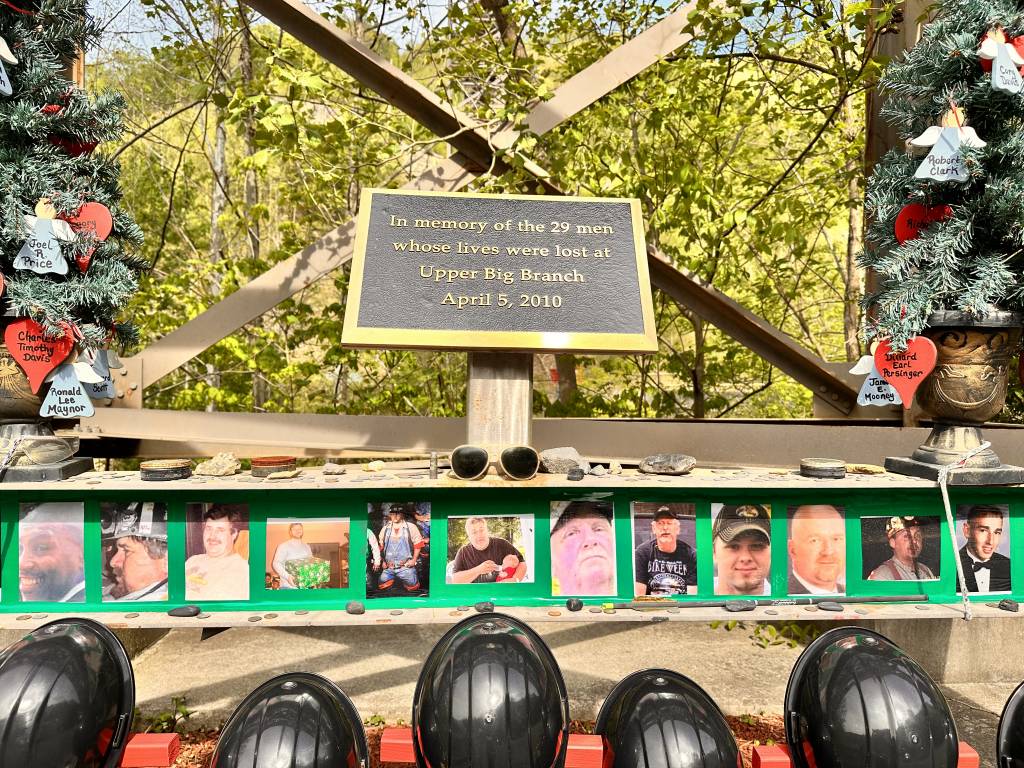

[pictured above] Memorial to the 29 mine workers killed in Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine explosion in April 2010

[pictured above] Memorial to the 29 mine workers killed in Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine explosion in April 2010

While in Naoma, our team got to witness original art from the “Voices of Appalachia” project, which combined portraits with hand-written accounts to share the stories of the everyday life, struggles, and perseverance of the people of Appalachia.

What can our movement learn from this?

Our conversations with CRMW illuminate the need for nuance and care in outreach and organizing, and to consider how context shapes interpretation of our movement’s own words. Junior noted that where he lives, “just transition” is seen as a term used by elites to continue destroying the environment under the guise of bringing in local jobs.

How does the extractive economy hold us hostage to a certain way of life? How can increased funding public services such as schools, food pantries, hospitals, parks, drug treatment centers and playgrounds allow for folks to enjoy living and thriving in Appalachia as we wean off coal?

And as communities built on coal start to wean from it, what gaps are there for the fossil fuel industry to capitalize on that lack of infrastructure and need for financial security and social wellbeing by pushing new projects that are equally as harmful?

Appalachia has long been a sacrifice zone for coal and for U.S. industrialization more broadly, and now everyone bankrolled by the fossil fuel industry—including Senator Joe Manchin—is ready to further sacrifice the people and land of Appalachia to profit off fossil gas. The battle wages on over the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a massive fossil gas project that the people of Appalachia have been fighting for years. Manchin and others like him weaponize the lived experience and single-industry economy of his home state, reframing harmful projects under the guise of clean energy, jobs, and “progress.”

Despite the systemic odds stacked against it, Appalachia represents the duality of so many local struggles. It is both a place that has been sacrificed over and over again for profit, and also a home of deep and continued resistance for over a hundred years which has moved the struggles of individuals into national pieces of our national movement infrastructure. Our fights are connected, and many of our best tools to fight them have been honed by groups like CRMW.

Follow along and stand with Coal River Mountain Watch at:

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/CRMWSTOPMTR

Twitter https://twitter.com/coalrivermtn?lang=en

Junior Walk’s Youtube https://www.youtube.com/@StopMTR