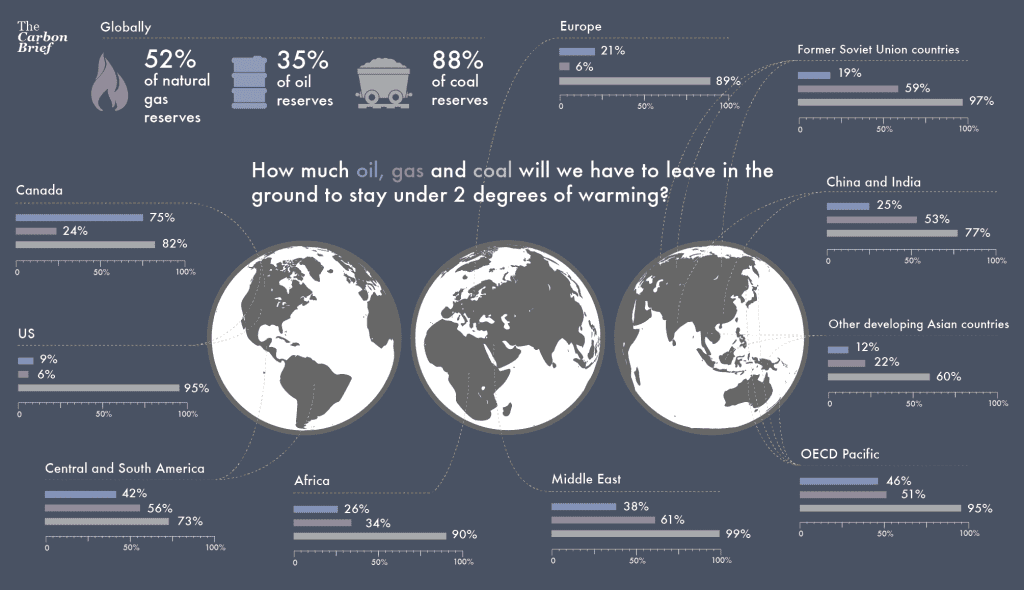

As if the signs of nature itself weren’t enough, this week the global community received another strong steer from Nature (with a capital N – the prestigious scientific journal) that keeping most coal in the ground is the only way to contain climate change. The numbers are particularly dire for Europe, where 21% of oil reserves, 6% of natural gas reserves, and 89% of coal reserves need to be left in the ground to stay under the internationally agreed red line of 2°C warming.

The Nature study is the first of its kind that breaks down carbon budget allocations not only by region, but by fossil fuel as well. And as one of the lead authors Dr Christophe McGlade clarifies, it is “not the only way forward and is by no means a prescriptive solution […] the research could feed into negotiations as a starting point for wider conversations about historical responsibility, equity and potential compensation mechanisms.”

From 89% to 100%

It becomes clear, when considering some of the assumptions that 89% number relies on, that the only way forward is for Europe to stop digging for more coal altogether – 100% of it – as soon as possible.

For starters, it would give us only a 50% chance to stay below 2°C, which still means widespread climate-induced destruction of the likes we’ve seen in previous months and years (from the fast-moving and hard-hitting floods in UK and central Europe, to the slow-burning plague of droughts in southern Europe).

Also, that number relies on every other region sticking precisely to their own carbon budget. How much can we count on, for starters, former Soviet Union countries leaving 97% of their coal in the ground, as per study’s calculations? This is hard to imagine, as Russia alone is on a coal expansion binge, with the country’s coal terminal ports to be increased by 300% over the next few years.

Lastly: we’re talking about reserves – fossil fuels that have been validated as feasible to extract both from a technical and economical perspective. Unconventional/extreme forms of further fuel extraction are a no go, despite some of the region’s governments thinking (and planning) otherwise.

The reality of leaving Europe’s coal reserves in the ground

When we’re in a hole, and we need to stop digging, two things usually help: diggers need to find a way to move on to the next thing they can do with their experience and skills, and – just as importantly – somebody needs to stop buying more shovels.

Coal finance is strong. Europe spends €10bn a year on coal subsidies. Germany spent €3bn supporting coal in 2012, more than any other EU country. And when it comes to Poland, the bloc’s poster kid for coal, Brussels has traditionally allowed big national firms to benefit from up to €1.7bn of funds in its current budget, according to recent research by CEE Bankwatch.

All of that funding is benefiting a dying industry. Just yesterday, the Polish government backed a rescue plan for Kompania Weglowa SA, the European Union’s biggest coal producer, which will cut jobs, close mines and get financial aid from state-owned power utilities in order to avoid total bankruptcy.

The risk, obviously, is that as the industry dies, it takes many of us with it – our public money, and our jobs. The Polish near-bankruptcy case alone will be the source of an expected 4,800 redundancies through 2016.

Despite this, lignite-fuelled power stations are still being built around the region, locking in consumption of the fuel for decades. There are 19 such facilities in various stages of approval, planning or construction in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Germany, Poland, Romania and Slovenia. Germany and the UK, the self-declared climate champions of the EU, come in first and third in the unenviable ranking of coal consumption in the electricity sector (Poland is a strong second).

Opposition is strong

“The coal renaissance in Europe was only a dream”. If that sounds like it’s coming from a green NGO press statement, think again. The International Energy Agency included that strong rebuttal in their recent Medium-Term Coal Report 2014. And it’s no surprise. European coal hit a seven year low, as the cost of mining and shipping the fuel dropped and demand from China, the world’s largest consumer of the fuel, is forecast to decline.

As if the strong signal from the market wasn’t enough, public opposition is spreading and strengthening. Last summer, thousands of people made their way to the German-Polish border region Lusatia, where Swedish state-owned energy corporation Vattenfall and Polish energy group PGE are planning to go ahead with expansion of their mining operations. People formed a human chain of 8 km connecting German and Polish villages that are supposed to make way for open-pit lignite mines.

In the last few months, an impressive uprising of Polish farmers, trade unions and community members in western Poland have been opposing plans by Polish energy company PAK, to build an opencast lignite mine in the Krobia and Miejska Górka region. When burned, this low-grade lignite emits more carbon dioxide than hard coal or crude oil, and twice as much as natural gas.

Next month, Global Divestment Day will provide another opportunity to, once again, highlight that fossil fuels – like coal – are history, and that the future lies in renewable energy. Institutions, like Nature study authors’ own University College London which has fossil fuel investments worth more than £14m, will be further pressured to stop funding climate wreckage and put their money where solutions already exist.

And this summer, from the 14th-16th August, activists from across Germany and neighbouring countries are inviting the public to join them in a convergence in the German Rheinland region – Europe’s biggest source of CO2 – calling for an end to coal. Here the coalfields stretch to the horizon and the humongous excavators surpass NASA’s Space Shuttle and Apollo Saturn V launch vehicle as the as the largest land vehicles in the world.

Europe needs a prompt and just phase out from coal. Its citizens demand it, markets continue giving signals in that direction, and anything other than leaving almost all of the region’s coal reserves in the ground is fundamentally incompatible with a livable future on our planet. As one of the authors of the Nature study remarks, it’s time to bridge the gulf “between the declared intention of the politicians and the policy-makers to stick to two degrees, and their willingness to actually contemplate what needs to be done if that is to be even remotely achieved.”