A group of women walked from Barisal, Bangladesh to Khulna to join up with the long march that was crossing the city that day. By long, I really mean long: this march traveled a distance of 145 kms, walking most of the way, meeting people, holding street meetings and telling people why the Rampal coal plant shouldn’t be built in the Sundarbans.

I asked the women what made them come so far. The youngest one in the group told me,” It’s matter of our survival. Without the Sundarbans, no one can protect us from cyclones and natural calamities. The coal plant will destroy our mother Sundarbans.”

Last week, I was part of the Long March in Bangladesh too. More than 800 people marched from Dhaka to southwestern Bagerhat. As we set out, hundreds of people assembled in front of the press club in Dhaka, and chants of “Long March! Long March!” resonated in the air.

People from all walks of life were there to march the more than 150kms to the Sundarbans. Their goal? Save their mother, the Sundarbans forest. The marchers were protesting the building of a 1320 MW Rampal coal plant. The thermal plant is barely 14kms away from a world heritage site — the Sundarbans forests — and being built on an area of over 1834 acres of land, most of which has been forcefully acquired from farmers and fish pond owners. The marchers called on the government to scrap the Rampal coal plant and halt industrial developments in the area that will inevitably damage the ecologically fragile Sundarbans forest.

Photo: Mowdud Rahman

The Sundarbans forest is home to various species of rare and endangered plants and animals, including the Gangetic Dolphins and the Royal Bengal tiger. The world’s largest concentration of mangrove forests is also in Sunderbans. The mangroves offer a natural barrier against cyclones, and Bangladesh faces a barrage of them every year. When I spoke to marchers about this, they said the strength of cyclones is increasing every year. With the proposed plant threatening the very existence of the forests, they say this is a battle to not only save the Sundarbans but also Bangladesh’s future.

In August 2011, Bangladesh’s Power Development Board (BPDB) and India’s state-owned National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) signed a memorandum of understanding to develop the Rampal coal plant. The joint venture company is known as Bangladesh-India Friendship Power Company (BIFPC). The Rampal coal plant will be built on an area of over 1834 acres of land which was mainly fertile farming land and fish ponds.

A fisherman goes home with his daily catch of fish but with the Rampal Thermal plant coming up, his livelihood is threatened. Photo: Joe Athialy

Most of the people in the march were students studying in colleges in Dhaka and some from other regions in Bangladesh. Over the four days that I joined them, one coherent message came across: there are alternatives to coal-based power generation, but there are no alternatives to the Sundarbans forest. Power can be generated from renewable energy sources but once the forest is gone, there is no coming back.

While passing from one city to another during the long march, I came across many battery-operated public transport vehicles. We call them “vans” in this part of the world. They are simple and the seat is made of wood. Previously, one had to paddle to move the vans, but now the vans are battery-operated and can be charged at home. Bangladesh is leading the solar energy revolution in South Asia. Close to 3.5 million households are being powered by solar home systems and every month 50-60,000 new households are connected. This makes me wonder: why power from coal?

I spoke to Umma Habiba Benojir during the march. Benojir is a leading student leader in Dhaka university and she said, “Bangladesh does need electricity, but not at the expense of destroying the Sundarbans. Bangladesh is our mother and the Sundarbans are the lungs. We won’t let anything destroy our mother nature”.

Many also complained about how the entire project has not followed proper norms to include consent from local farmers and fishermen who depend on Sundarbans. The marchers said the Environment Impact Assessment of the project should be done afresh and by an independent body, as they fear any government agency won’t be neutral.

Live from long march in Bangladesh: A resistance song to #savesundarbans from destruction. pic.twitter.com/x03BUMkTGp

— 350 dot org (@350) March 12, 2016

#savesundarbans march from Jessore town with slogans of: Sundarbans is our mother, we renew our vow to protect it pic.twitter.com/nwcJ0uCGci

— 350 dot org (@350) March 12, 2016

The @UNESCO site #Sundarbans is being threatened by coal, but thousands are marching right now to #savesundarbanspic.twitter.com/eYnu9mT9XK

— 350 dot org (@350) March 13, 2016

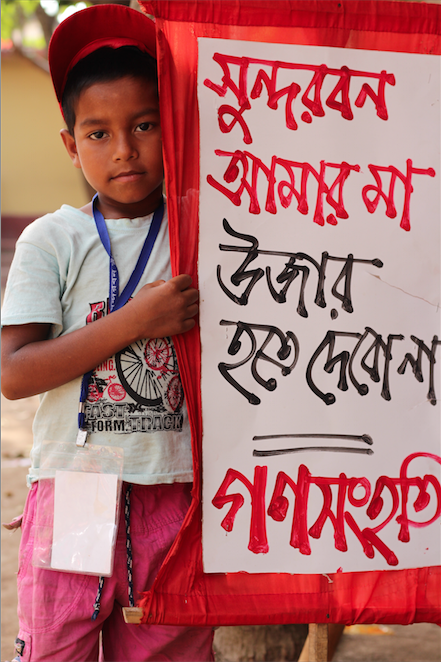

The youngest marcher holding a banner that says,”Sundarbans is our mother, we won’t let it get destroyed.” Photo: 350.org

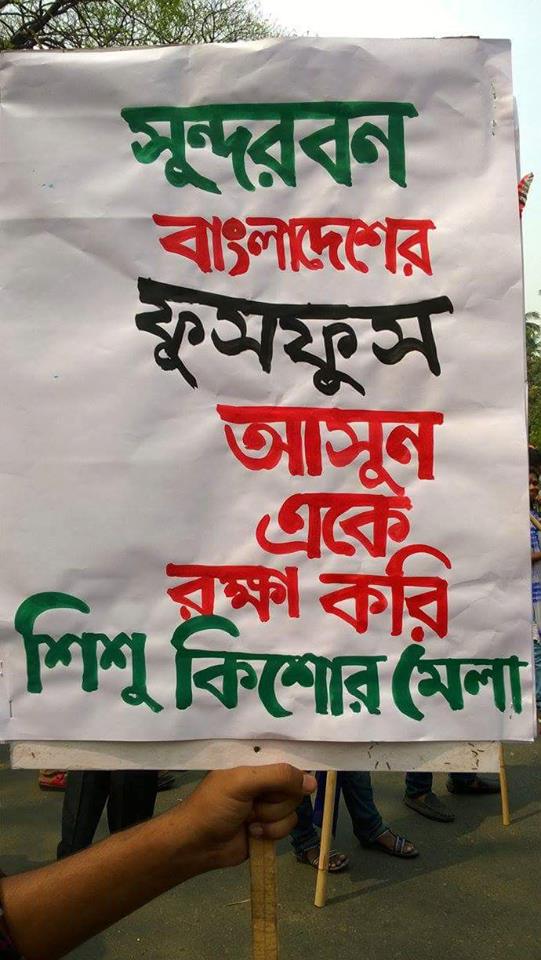

The Sundarbans is the lungs of Bangladesh. Let us all protect it. Photo: 350.org

The coal plant will need to import 4.72 million tons of coal per year. Over the course of two years, four cargo vessels have sunk in rivers inside the Sundarbans, including a oil tanker carrying 350,000 litres of furnace oil. The latest incident happened on March 19, when a large cargo vessel carrying 1,245 metric tons of coal sank in Sela river inside Sundarbans. If the Rampal coal plant is built, we will see a dramatic increase in the shipping of coal — a disaster for both the Sundarbans and Bangladesh that’s waiting to happen.

Freight ships are already increasing in numbers on Poshur River. In the last year alone there has been a major oil spill followed by a coal spill. Accidents like these are likely to increase if the Rampal coal plant is built in Sundarbans. Photo: 350.org

The marchers also alleged that land for the plant was forcefully acquired from farmers and fishpond owners. I found this to be true, as after the march I went to speak to Susanta Ghosh, the leader of Krishi Jami Rakkha Committee (Farming Land Protection Committee). He told me that his 65 acre land in Rampal, where the coal plant is being built, was forcefully acquired in 2011 when the project work began. When he and other farmers resisted and formed a grassroots movement against it, they were slapped with false charges that included arson, dacoity, and damaging public property. His movements were restricted and even his family members were harassed by local police. He finally gave up and paid bribes to the local cops to withdraw the charges. Even though he speaks to international media often, he says his movements are strictly monitored.

As I walked with the marchers for four days I noticed the strong sense of unity and camaraderie among the marchers. They would often break into songs praising the beauty of the Sundarbans forests and the duty to protect it from destruction.

“Ami Charbo Na,

Ami Charbo Na,

Amar Sundarban”

The song means, I won’t leave my Sundarbans. The forests are worth gold. Local resistance against the plant has been subdued due to state repressions, and so this march offered a space for activists to voice their opposition to the Rampal coal plant and question the very model of development that is being ushered in. Marches, rallies, and songs have often been used in the global south to protest state repression and against corporate grabs of forests and resources. The first long march in 2013 and the subsequent protests resulted in French banks walking out of the project. The recent long march came just a few weeks before a slated UNESCO visit to assess the environmental impact of the project on the Sundarbans heritage site, thereby putting more pressure on the decision makers.

If these demands are not met, the march organisers plan to hold nationwide rallies, hartals, and sit-ins to force the government to meet their demands. The marchers and the local resistance leaders are also going to meet the UNESCO team that is visiting Sundarbans now.

Even during low tides, fishermen can be seen spreading out their nets in the Poshur river to catch fish. But their livelihood is in danger with the building of the Rampal coal plant as the hot water from its cooling tower will be discharged in the river which will kill all marine life. Photo: 350.org