By Deirdre Smith, Strategic Partnership Coordinator

It was not hard for me to make the connection between the tragedy in Ferguson, Missouri, and the catalyst for my work to stop the climate crisis.

It’s all over the news: images of police in military gear pointing war zone weapons at unarmed black people with their hands in the air. These scenes made my heart race in an all-to-familiar way. I was devastated for Mike Brown, his family and the people of Ferguson. Almost immediately, I closed my eyes and remembered the same fear for my own family that pangs many times over a given year.

In the wake of the climate disaster that was Hurricane Katrina almost ten years ago, I saw the same images of police, pointing war-zone weapons at unarmed black people with their hands in the air. In the name of “restoring order,” my family and their community were demonized as “looters” and “dangerous.” When crisis hits, the underlying racism in our society comes to the surface in very clear ways. Climate change is bringing nothing if not clarity to the persistent and overlapping crises of our time.

I was outraged by Mike Brown’s murder, and at the same time wondered why people were so surprised; this is sadly a common experience of black life in America. In 2012, an unarmed black man was killed by authorities every 28 hours (when divided evenly across the year), and it has increased since then. I think about my brother, my nephew, and my brothers and sisters who will continue to have to fight for respect and empathy, and may lose their homes or even their lives at the hands of injustice.

To me, the connection between militarized state violence, racism, and climate change was common-sense and intuitive.

Quickly understanding interdependence and connectedness here, and often elsewhere is, in part, the result of my experience of growing up black in America, and growing up in New Mexico, a place ravaged by climate impacts. New Mexico is, as Oscar Olivera noted, showing the early signs of what sparked the Cochabamba Water Wars, yet another example of how oppression and extreme weather combine to “incite” militarized violence.

The problems of Cochabamba and Katrina are not just about the hurricane or the drought – it’s what happened after. It is the institutional neglect of vulnerable communities in crisis, the criminalization of our people met with state violence, the ongoing displacement of New Orleans’ black residents through the demolition of affordable housing for high-rise condos — that all adds up to corporations exploiting our tragedy using the tools of racism, division, and dehumanization. (Naomi Klein calls it the Shock Doctrine.) And it’s also about what happened before too: how black and brown communities have coal refineries, tar sands, and gas wells in their back yards to extract fossil fuels in the first place.

These divisions imposed on us prevent us from building the movement we need to create a new future for ourselves, a future where we have clean energy that doesn’t kill us, and creates jobs that provide dignity and a living. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, black and brown people were seen as “disposable,” and the powers-that-be sought to divide us by once again painting the victims and heroes as villains.

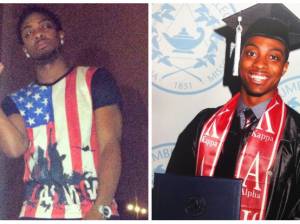

The hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown trended during the past week in reaction to the media’s portrayal of Mike Brown and countless other victims. Black folks asked: if I was killed by police, how would I be portrayed? It illustrated how a racist and victim-blaming cultural narrative is central to how the media responds to the victimization of a vulnerable community in crisis.

A discourse that dehumanizes and blames the victims makes black and brown communities even more vulnerable than they already are in the wake of climate disasters. If extreme weather is about droughts, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires, the way people get treated in the wake of disaster is about power.

Demonization and the illusion of the “other” allows mainstream US to feel unaffected and disconnected to the employment of unacceptable and institutionally supported militarized violence. If we hope to build anything together and employ our combined power we must deny that anyone is an “other” – denying this pervasive cultural norm isn’t easy but it’s a central challenge we face.

We’re all impacted by climate change, but we’re not all impacted equally.

Communities of color and poor communities are hit hardest by fossil fuel extraction, as well as neglected by the state in the wake of crisis. People of color also disproportionately live in climate-vulnerable areas. Similarly, state violence should concern us all, but the experience of young black men in particular in this country is unique. Those of us who are not young black men must step up to the challenge of understanding that we will likely never experience that level of demonization. That kind of solidarity is what it takes to build real people power — the kind of power that stands up unflinchingly to injustice, and helps us all win our battles by standing together.

This is difficult work. Some of it requires listening and working with racial justice organizations, and some of it requires introspection, questioning what we have been taught, and healing from internal oppression. Part of that work involves climate organizers acknowledging and understanding that our fight is not simply with the carbon in the sky, but with the powers on the ground.

Many people have pointed out that the climate movement needs to understand our internal disparity of power too: between mainstream and grassroots organizations, between people of color and white folks, between the global north and the global south. We need to account for these things if we truly want to build the diverse movement leadership that we will need to win.

The events in Ferguson offer an important moment if you’re a climate organizer, looking around the room, wondering where the “people of color” are. It’s a time to to dig deep and ask yourself if you really care why — and if you are committed to the deep work, solidarity, and learning that it will take to bring more “diversity” to our movement. Personally, I think the climate movement is up to this necessary challenge.

It isn’t incidental, it’s institutional, and it’s rooted in history.

I can’t stress enough how important it is for me, as a black climate justice advocate, as well as for my people, to see the climate movement show solidarity right now with the people of Ferguson and with black communities around the country striving for justice. Other movements are stepping up to the plate: labor, GLBTQ, and immigrant rights groups have all taken a firm stand that they have the backs of the black community. Threats to civil dissent are a threat to us all. We’ve seen this kind of militarized police violence in the environmental movement before: in the repression of the Global Justice Movement, pioneered by police with tanks on the streets of Miami during the Free Trade Area of the Americas protests in 2003, to name just one example.

Scene from the militarized police repression of environmental and global justice activists in Miami 2003. Since pioneering this model, local police forces across the country have been given military-grade weapons with little to no training.

It has happened to our movements before, and it will happen again. As James Baldwin expressed, “if they come for you in the morning, they will come for us at night.” But solidarity and allyship is important in and of itself. The fossil fuel industry would love to see us siloed into believing that wecan each win by ourselves on “single issues.” Now it’s time for the climate movement to show up– to show that we will not stand for the “otherizing” of the black community here in America, or anyone else.

We have a lot of learning to do about how to come together, but we are in process of learning how our fights are bound together at their roots. If we knew everything we needed to know about navigating the climate and ecological crises, we would have done it already. Now is a time to stand with and listen to the wisdom of our allies in movements that are co-creating the world we all want to live in.

As crisis escalates, as climate change gets worse, we better get ready to see a whole lot more state violence and repression, unless we organize to change it now.

The first step to understanding is listening. The second step is digging.

I could tell you all day about the brilliant and strategic analysis and leaders that exist in historically oppressed communities. I could tell you…but your path to understanding why solidarity is important is your own. Don’t miss this opportunity to dig in and show up. Don’t miss this opportunity to leverage our power together. If we mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis it, will be because we understood our enemies and leveraged our collective power to take them down and let our vision spring up. Take a moment today to read the demands of the Dream Defenders, Freedomside, and Organizing Black Struggle. Read about solidarity and white allyship, and identify anti-blackness showing up in your spaces. Take a moment today to really think about how we really should confront the climate crisis and ask yourself if you’re willing to dive into the long haul and complex work it will take.

I believe in us.

I am grateful that amidst all my anger, frustration, sadness, determination, and exhaustion that I am left with one resounding thought: I believe in us.

Doing climate work takes a lot of courage, and I am endlessly inspired by my comrades’ and colleagues’ abilities hold the contradictions, complexity, and overwhelming reality it is to take on this challenge. I am excited by the deepening and aligning I’ve been seeing happening in cross-sector movement spaces over the past year especially. The more complex (and less comfortable) we allow ourselves to be, the more simple things actually become: we are in this together and our fights are connected. We don’t know everything by ourselves, but together we know enough.