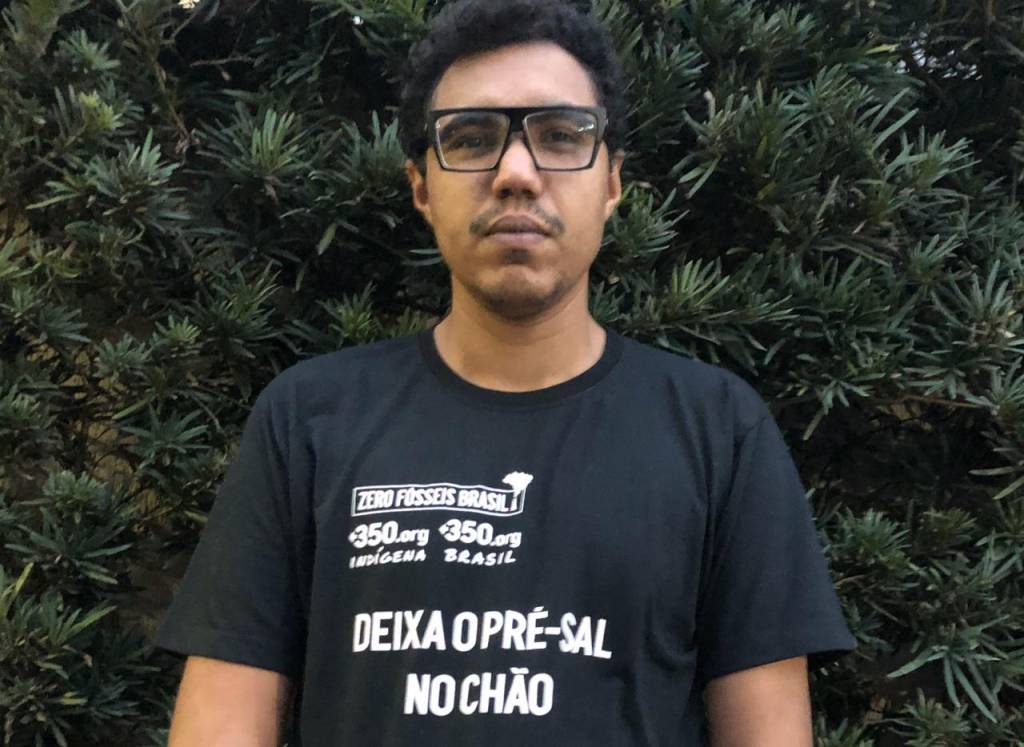

Gabriel Perez dos Santos is a young black journalism student. He has been involved in several actions with 350.org Brazil covering the fight against fossil fuels and the climate crisis.

Gabriel Perez dos Santos is a young black journalism student. He has been involved in several actions with 350.org Brazil covering the fight against fossil fuels and the climate crisis.

Marches around the world show us that Black lives matter. The deaths of George Floyd, João Pedro, and so many other victims of police violence reveal countless more challenges for black people. And many of these challenges are also present in the fight to protect the environment and stop climate change.

At the beginning of this year, one case drew attention: at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Young activists attended to alert governments to the climate crisis and urge them to take action. Among them was Vanessa Nakate, 23, from Uganda, one of the only black activists present at the protest. Nakate’s struggle became known when she was cropped out of a photo from a photo alongside Greta Thunberg and other white activists by the Associated Press. When asked about the case, the young woman confessed that she felt the definition of the word ‘racism’ for the first time.

This occasion highlights the invisibility of people of colour in the environmental movement, which is often associated with stereotypes of middle-class white people. But we forget that the black population, along with Indigenous peoples, are most often the ones subjected to the consequences of environmental destruction. They are the ones who suffer from the impacts left by polluting industries. They are the ones who have to leave their lands as climate refugees because of climate disaster.

In the late 1970s, activist Dr. Robert Bullard followed the case in a black community dealing with problems from irregular disposal of toxic waste near their neighbourhood. With this case, Bullard – now considered the father of the environmental justice movement – began to name the correlations between race, environment and poverty. These concepts helped to shape further evidence and theories on environmental racism.

Environmental racism? The term is used to refer to racial discrimination embedded in development and environmental policymaking that burden communities of colour to a disproportionate number of risks to health and quality of life. It turns out that most of the people who live under terrible sanitary conditions, polluted areas, or unsafe housing and workplaces are black, brown and Indigenous people.

These are just some of the social problems imposed on black communities. They also include the high homicide rates, particularly for young people. And when we look at representation in leadership positions, black, brown and Indigenous people fight the invisibility of structural racism on a daily basis. The question, of course, is not a simple one. People of colour know how much the climate crisis is affecting their lives, but we must understand that the struggles for racial equality and environmental justice make up the same program.