This spring a wave of actions rolled over six continents under the slogan Break Free from Fossil Fuels (#BreakFree2016). People got together to block coal mines and drilling platforms, as well as oil companies’ offices and banks that invest in the fossil fuels industry. Their objective was simple: to send the clear message to governments and businesses alike that implementing the Paris deal and stopping dangerous climate change is only possible by reducing the fossil fuel extraction right now. Unfortunately, the larger part of Eurasia, including Russia and the Middle East, remained a blank spot on the map of the recent protests. However, the success of the global anti-fossil fuel campaign largely depends on what happens in this and other blank spots, where the bigger share of the world’s fossil fuel resources is concentrated.

Leave fossil fuels in the ground!

The message of the campaign against fossil fuels was simple and correct: if the promises to stop climate change voiced at the Paris summit are more than just words, then the fossil fuel extraction must be scaled down, here and now.

Picture: Reclaim the Power

The campaign’s geography is impressive: a wave of actions rolled from Europe to the faraway Australia.

Orange – #BreakFree2016 actions. Green cross marks Komi region

However, a closer look at the map of actions makes it clear that there are blank spots. One of the largest spreads across half of Eurasia: Russia, China, the Middle East… What was happening here during Break Free?

Komi: inside the “blank spot”

The Izhma Komi are a small nation (around 15,000 people) that lives in the northern Komi Republic in Russia and speaks one of the Finno-Ugric languages. For them, like for many Finno-Ugric people, harmony with the fragile northern nature has always been a condition for survival. But now this harmony is broken. The reason is easy to find: the lands of the Izhma Komi have been grabbed by Lukoil, one of Russia’s largest oil companies.

In April 2016 busy days started for the Save Pechora Committee, one of the few NGOs that still remains in the North of Russia, in spite of the recent years’ draconian laws against environmental organizations. As ice melted in the Pechora, Izhma and Yarega rivers, instead of the northern crystal-clear streams breathing with life, the Izhma Komi who live there saw dirty currents of black liquid. It got stuck to boats, people’s hands and clothes, enshrouding the feathers of the water birds that came…

“What happened in Yarega is beyond the memory of either Ukhta or Izhma. This is something that stands between a huge catastrophic oil spill on the Pechora river in 1994 and the 2014 Kolva river spill. For two days, a solid oil film floated down the Izhma river and there was an unbearable smell of oil products. After this, it was not unusual to catch fish that smelled and tasted of petroleum products, and the hunted ducks were covered with oil. Taking into account that fractions of heavy Yarega oil reached the riverbed in the depth of the flow, the consequences will be lasting long,” stated Nikolay Bratenkov, a representative of the Save Pechora Committee.

The scale of the disasters here is truly frustrating. For example, the 1994 year oil spill was reportedly mentioned in the Guinness Record Book as the worst one by that time.

Photo: Greenpeace

Local activists discovered that the spill can be traced back to the Yarega industrial site of the company. Lukoil’s security would not let them further, although hectic attempts to cover up the evidence were visible from afar.

Since the 15th century, when their lands were taken by Russia, the Izhma Komi tried hard to be friends with Moscow, avoiding participation in conflicts and revolts. But this time their patience ran out, and the people took to rallies and pickets in the towns and villages of Ukhta, Tom, Izhma, Mutnyi Materik.

Photo: Save Pechora Committee

Authorities reacted peculiarly. No one rushed to investigate how hundreds of tons of oil ended up in the river, yet the Izhma Komi’s protests became an object of close attention for the security agencies. In the city of Usinsk, protesters were summoned to “an interview” with FSB (the security police, better known by its former name KGB). In the towns of Mutnyi Materik and Ust’-Usa the authorities threatened to organize “troubles” for all who will be pictured at the protest action. In Ust’-Usa the rally was banned altogether (in Russia, any public gathering must be authorized, and can ultimately be rejected on countless grounds, often false).

In spite of the pressure, the Izhma Komi have no intention to stop. Their most immediate goal is clear: mitigation of the spill’s consequences and punishment of those responsible. While the Izhma Komi do not hope to halt oil drilling in their land, they consider it an imminent evil. According to poll results, the majority of the locals believe that oil extraction has brought them more harm than benefit.

This case is hardly unique, in fact. Vladimir Chuprov, Greenpeace Russia’s energy program director, said: “The Arctic Ocean receives about 10,000 tons of petroleum products from the Pechora river annually, according to the Russian Hydro-Meteorological Service. Lukoil-Komi is the principal ‘supplier’ of oil into the Pechora and informs of about 6,000 tons of oil leaked into the environment every year as a result of oil pipeline accidents. We have to remember that oil companies have been traditionally underreporting the scope of spills and the number of accidents.”

Actions and “barrels”

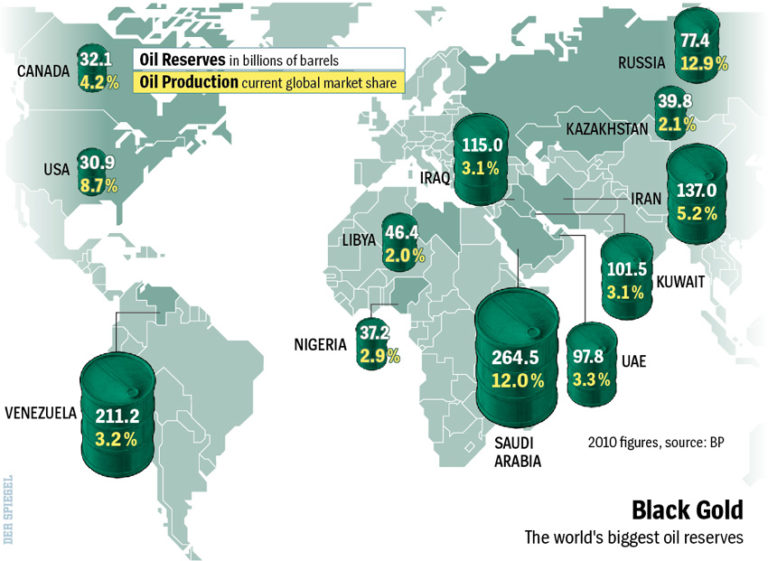

Perhaps the gatherings of the Izhma Komi look less impressive in comparison with the colorful actions of Break Free. But in the context of the global struggle, their importance is tremendous. And it is again geography that matters. Remember our “blank spots” map? Here is another one: these are the explored oil resources in the world. Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Venezuela – most of the “barrels” are placed precisely where colorful protests are yet to be seen. Instead, as we see, we find the Izhma Komi people with handwritten placards, standing up practically on their own against the pressure of the extraction companies and the repressive regimes.

Picture: Der Spiegel

Once, during the democratic spree of the 1990s, the Save Pechora Committee managed to succeed in negotiating with the authorities and the oil companies. Their words had weight in the most important matters, from establishing the borders of national parks to closing nuclear testing sites at Novaya Zemlya. But the situation is now changing dramatically: Russia’s regime gets ever harsher. This is not without help of the ceaseless flow of oil money from Europe and Asia. This phenomenon has been long known as the “resource curse”: the resource rent often contributes to strengthening the most backdrawn tendencies of a society. So, the coincidence of the “barrels” and the blank spots is likely far from incidental.

“Now we don’t have the possibilities to negotiate seriously with either the government or Lukoil. They don’t hear us. They ignore us. The only way to influence them is in the rallies, marches, pickets, demonstrations. Even then, every month the restrictions on public events get harsher, to wrest from the hands of the public their last means to influence the authorities. Perhaps in the spiral of history we are returning to slavery at the modern level”, Nikolai concludes pessimistically.

How to wipe a blank spot off the map?

Any way out from this? Is it possible that those who say that civic efforts to fight the fossil fuel extraction in Europe, America or Australia will only play into the hands of the authoritarian regimes sitting on the proverbial barrels are right?

Maybe not, but we need an efficient method to color those blank spots. And the method is pretty simple. It is called solidarity. Solidarity with those who are fighting for progressive changes inside our “blank spots”, from Russia to Venezuela. The profit of Lukoil depends directly on how much oil it manages to sell in Europe. The Izhma Komi understand this too, as they admit their only hope in their unequal fight is on “public outcry at a global scale, the support of international society, and their capacity to influence international banks crediting Lukoil and the like...”

Greenpeace is the organization currently helping the Izhma Komi the most. Admitting his organization is facing problems in Russia, Vladimir Chuprov sees the potential of change for the better: “The Izhma Komi actually have some positive cases. After a public campaign led by NGOs for many years, Lukoil has made a separate agreement with the Izhma Komi national organization, Iz’vatas, on social support and environmental policy issues that benefit the Izhma district. So, if the company cares about its image, then such results are possible.”

The image of the company is perhaps of key importance here. Hardly shying away from “dirty” projects in their own countries, companies like Lukoil strive to demonstrate their clients and the Western public a completely different picture. Perhaps, the very success of the idea of civic action against the industry of the fossil fuels depends on whether the Western consumers can be made to think about the true price of the oil, gas and coal, which so easily coming into their world out of our “blank spot”.