This is a guest blog from TierrActiva, a network of youth climate activists in Peru. This article was originally posted in Spanish in LaMula.pe.

Notes for civil society organizing against the climate crisis

When we talk about climate change and the actions we must take to address it, we usually rely on two concepts or areas of action: mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to the impacts of emissions we are unable to mitigate.

In the context of the international climate negotiations (COP), it is easy as civil society organizations to focus on tackling climate change from the perspective of “mitigation and adaptation” and its more technical aspects: memorizing acronyms and figures, talking about solutions to reduce the equivalent of gigatons of carbon dioxide or parts per million concentrations, and often, prioritizing the search for global solutions, technological or the like.

Navigating this technical language allows us to understand, communicate, influence and generate proposals for action within the framework of national and international policies. Amid all this, however, it is crucial to recognize that each technical proposal, each mitigation mechanism, each adaptation measure has an impact. Reveals a stance. In a world and system marked by historical power relations, it will necessarily benefit some and not others. It is necessary to recognize, explain and question this by introducing our own terms to the conversation: a language of clear political stances, understanding in politics, such as life, the scope of power relations and justice.

Just as the world of mitigation and adaptation is not neutral, neither are our approaches. The positions we take as civil society organizations have a context and historical background, as well as people who struggled and strive to build them. TierrActiva from Peru, published this first article as a general introduction and recognition of two key concepts within our political stance: Climate Justice and Intersectionality.

What is Intersectionality?

Intersectionality focuses on how social categories such as gender, race, socio-class, ability, sexual orientation, religion, and other aspects of our identity interact on multiple levels, contributing to discrimination, exclusion, social inequality and systemic injustice.

To take an intersectional approach seeks to make visible and address the various privileges and oppressions that we all have in order to build an activist movement that is more just, inclusive and coherent. As a concept, it was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, in the context of black feminist struggles in the US.

What is the relationship between Intersectionality and Climate Justice?

In recent years, climate justice organizations in various regions of the world have begun to take an explicit intersectionality focus, with different challenges and results. Below is an excerpt that describes some of the reasons why intersectionality is relevant to such movements:

“In the climate justice movement, an analysis of intersectionality helps explain why we cannot simply fight for a greener, cleaner version of this current system by reducing emissions, stopping deforestation and shifting to renewable energies like wind and solar. The collapse of our ecosystems and disasters like hurricanes and oil spills have always impacted certain people more than others. Usually, it’s also those very communities who have less access to resources –– such as reliable housing –– that would help them survive the economic devastation that comes with ecological collapse. (…)

We must remember: Intersectionality isn’t only structural. It is also personal. Most of us carry within us overlapping layers of privilege and oppression. As a migrant woman of color born into a working-class family, I may understand what being on the front lines of multiple oppressions looks like, but I also have the privilege of the economic and social access that my college education, mixed race and part of family’s transition into the middle class have afforded me. Glossing over these very real distinctions ends up allowing historical oppressions to continue to play out unchallenged, minimizing, silencing and erasing certain voices.

On a bigger scale, we need to provide resources and access to those who don’t have them in ways that are not tokenizing. Organizers have to stop talking of “empowering” people on the margins, as if they didn’t have their own power already. It’s about getting out of the way for others to take up space while valuing the fact that power already exists in marginalized communities. It’s also about understanding our own identities, where we benefit from the system and where we don’t — and taking responsibility for our layers of privilege in how we move about the world. It’s about established organizations being watchful of the inequalities they perpetuate, especially in terms of access to resources and to the job market within the non-profit complex. Through all of this, we have to commit to working slowly in spite of the urgency of our crises, and to holding ourselves accountable when destructive dynamics arise.”

What is Climate Justice?

Climate justice is a stance much more common and known compared to intersectionality within climate change movements; however, for this reason, the term may refer to different and even conflicting objectives. Here are some key ideas of what climate justice is according to the main groups that have developed it in the context of the climate negotiations: groups and grassroots networks like Climate Justice Alliance, Climate Justice Now! and The Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice.

The movements for climate justice seek to address the inequalities and discrimination that are generated or fueled by the impacts of climate change.

Therefore, a climate justice approach places at its center populations that are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. At the same time, climate justice seeks to recognize common but differentiated responsibilities between countries with different levels of development, demanding that the historic debt by the largest emitters of CO2 is honored. For example, this means to differentiate what each country should invest towards international funds on adaptation to climate change.

In the context of the negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), or the annual COP, groups and countries with a focus on climate justice oppose 2 degrees Celsius as the proposed ultimate limit to global warming, and propose 1.5 degrees instead. Why? In general, to talk about a global average ignores the differentiated impacts that the average may have on the most vulnerable populations – in this case, 2 degrees would mean a warming of 3 degrees or more in parts of Africa, with devastating consequences, and would mean the complete sinking of island nations in the Pacific Ocean.

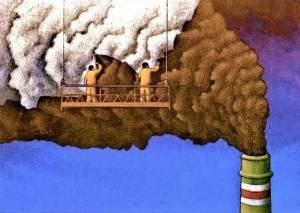

Another key aspect of the movement for climate justice is the rejection of false solutions to climate change, and the support for alternatives and answers that address the climate crisis from communities, taking into account the roots of the problem. False solutions are those responses to climate change based on “savior” technologies and market solutions, including for example the carbon credit market. Carbon credits are based on the principle that companies can pay to continue polluting, while the money from the credits supports conservation initiatives in other places. As has been investigated and reported on many occasions, this logic simplifies the complex reality of the climate and environmental crisis, perpetuates the unsustainable industrial model, gives false compensations, and distracts from what is really needed to address the problem.

An effective response cannot depend on what caused the climate crisis–the system crisis–in the first place: fossil fuels, mega industry, the search for private profit, and the private market. For example, in regards to adaptation and mitigation to climate change in the field of agriculture, the climate justice movement Via Campesina proposes:

“Farmers and indigenous systems of agriculture, hunting, fishing and herding that help care for the earth and food supply must be adequately supported with public funds and resources without condition. Market mechanisms, such as carbon sales and environmental services, should be removed immediately and replaced with actual measurements. To stop pollution is a duty that no one can avoid by buying rights to continue destroying. (…)

We repudiate and denounce the green economy as a new mask to hide increasing levels of corporate greed and food imperialism in the world, and as a brutal means to wash the face of capitalism, which only imposes false solutions such as climate-smart agriculture, carbon trading, REDD, geoengineering, GMOs, agrofuels, biocarbon, and all market solutions to the environmental crisis.

Our challenge is to restore another way of relating to nature and among communities. That is our duty and our right and therefore we continue to fight and are called to continue fighting tirelessly for the construction of food sovereignty, comprehensive agrarian reform and the recovery of indigenous territories, to end the violence of capitalism, and to restore farmer and indigenous agro-based production systems.”