Russian society’s perception of global climate change is a complicated matter. Russian climatologists have been unambiguously claiming for a long time that it has been affecting Russia 2.5 times faster than the world average, and that human activity is its main cause. At the same time, most Russians hardly perceive climate change as a serious problem. Even when facing the outcome of the climate crisis, people are rarely inclined to link the causes with the consequences. Moscow was engulfed by smog a few times this autumn. The unnatural combination of cold, mixed rain and snow, smog and the smell of burning literally shouted that something in nature had gone wrong. Eventually, it turned out that the burning was in the peatlands of the Briansk region’s Chernobyl trail.

Burning radioactive peatbog. Courtesy of Greenpeace, Gazeta.ru https://www.gazeta.ru/social/photo/dym_s_chuzhbiny.shtml#!photo=0

The Moscow air came under the threat of radioactive precipitation preserved in the peat since the Chernobyl disaster. News and discussions about the radioactive smog predictably caused much interest in society and were debated by bloggers and media. But hardly anyone mentioned what had really caused the forests and bogs in central Russia to dry out and thus burn (something which will continue). This cause is the climate, or, more precisely, its change. The very term “global warming” is perhaps partly responsible for this. While it is correct in describing the situation across the planet in general, this does not seem that frightening for the inhabitants of icy Russia. The fact that the “warming” means the destruction of the millennia-old climatic balance which is closely tied to processes in the whole of nature is still understood by only a few. But there is another aspect that arguably matters more. One peculiarity of climatic processes is that they happen slowly and gradually in the “latent” phase, unnoticed by most people. But when the slow change leads to another disaster, what happens is perceived as an unfortunate coincidence or someone’s negligence: let’s try to figure out what has brought the smoke from the radioactive peatlands this time. Once, Soviet schoolchildren were instructed to keep a “weather journal” and note which days were sunny or rainy, what the temperature was, whether there was snow. Today’s schoolchildren have much less difficulty; it’s enough to go online. Back in the day, many of us believed there could be no task as boring as this. But if you leaf through the 2014 data for central Russia, it evidences the range of climatic anomalies that led to the wildfires. It simply could not have happened otherwise. But let’s take it in order. New Year 2014 was greeted in Russia as expected, with snow and light frost. Skis, sledges, snowball fights and snowmen… and then it was suddenly over when a week of steady warm weather started in mid-January.

This picture was taken on January 11 in the Ruza rayon of Moscow oblast. Is this what “the Russian winter” looks like now?

What happened turned out to be just the beginning: the mid-January snow was almost completely wiped out by a thaw that came on February 12. The layer of snow was just 1 cm thick by the end of winter, instead of the usual 30 to 40 cm. Last winter was unique for Russia: the snow cover never arrived, while the fresh snowfall would melt within a month.

Central Russia was left without almost any snow in February 2014. Courtesy of Nashaplaneta.su https://nashaplaneta.su/blog/vmesto_vjug_i_metelej_prodolzhitelnaja_ottepel/2014-03-03-17769

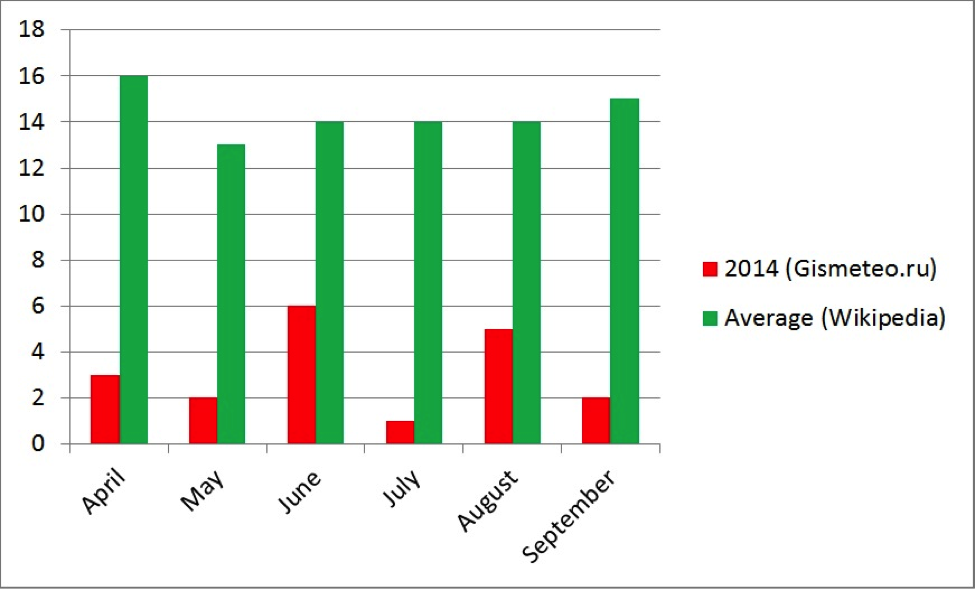

However, many people were sincerely happy with this “European soft” weather. Now the problem is that the climate here is much more continental, with relatively low precipitation in the summer. Typically, the soils in Central Russia literally bathe in melted snow water collected in the snow cover during the 5 to 6 months of winter. This moisture would help vegetation to start growing and to survive the relatively arid summertime. On top of that, it would fill the bogs, safeguarding them from ignition. In 2014, the drought had already been “preprogrammed” in March, even if the summer happened to be ordinary. Meanwhile, the sequence of climatic anomalies continued. In April, the air warmed up to +23 C with only three rainy days, while it should have averaged at least 16. May had just two rainy days (12 is the “norm”). The normal (average) number of rainy days and their actual number in the 2014 warm season are shown in this diagram.  Especially noteworthy are the one rainy day in July and two in September, numbers more relevant to Sinai rather than Moscow. Rather than wondering why the wildfire smog came to Moscow, it is more appropriate to wonder why it happened this late. The situation was likely somewhat improved by another weather anomaly, as the temperature fell below +10 C in late June and showers came. I will take the risk of suggesting that the fires kept burning at least during the whole of August and September. Mixed rain and snow after the abrupt October cooling had the effect of a bucket of water poured onto a burning fire; it brought smoke, the smoke mixed with fog to create smog, and this smog was experienced by the inhabitants of the large cities. The worst point is that there will be more such fires every year, and not just thanks to burning peat. For example, a significant part of the forests around Moscow are of the taiga type with a predominant fir which cannot survive climatic changes and perishes en masse. The dead fir trees are yet another source of the threat of fire (although luckily, they are not radioactive). You may ask what should be done. Here we have to go back to the beginning. The first stage of a problem’s solution is always awareness. Our task is to help ordinary Russians to see the link between the climatologists’ global forecasts and the problems they are dealing with in their everyday life. It is only when society grasps the gravity and scale of the threat that the opportunity will come to halt climate change.

Especially noteworthy are the one rainy day in July and two in September, numbers more relevant to Sinai rather than Moscow. Rather than wondering why the wildfire smog came to Moscow, it is more appropriate to wonder why it happened this late. The situation was likely somewhat improved by another weather anomaly, as the temperature fell below +10 C in late June and showers came. I will take the risk of suggesting that the fires kept burning at least during the whole of August and September. Mixed rain and snow after the abrupt October cooling had the effect of a bucket of water poured onto a burning fire; it brought smoke, the smoke mixed with fog to create smog, and this smog was experienced by the inhabitants of the large cities. The worst point is that there will be more such fires every year, and not just thanks to burning peat. For example, a significant part of the forests around Moscow are of the taiga type with a predominant fir which cannot survive climatic changes and perishes en masse. The dead fir trees are yet another source of the threat of fire (although luckily, they are not radioactive). You may ask what should be done. Here we have to go back to the beginning. The first stage of a problem’s solution is always awareness. Our task is to help ordinary Russians to see the link between the climatologists’ global forecasts and the problems they are dealing with in their everyday life. It is only when society grasps the gravity and scale of the threat that the opportunity will come to halt climate change.

Author: Mikhail Matveev

Translation from Russian: Roman Horbyk, 350.org Translation Team